The buyer calls on a Wednesday afternoon. The order was placed four weeks ago, production is scheduled to begin next Monday, and the target delivery date is three weeks out. But the buyer's internal timeline has shifted. The corporate event moved forward by ten days, and now the drinkware needs to arrive two weeks earlier than originally planned. The buyer asks if the factory can "expedite" the order. The buyer offers to pay a rush fee—twenty percent, thirty percent, whatever it takes. The assumption is clear: money can compress time.

This is where the conversation becomes difficult, because the buyer is operating under a premise that does not align with manufacturing reality. The buyer believes that production lead time is a function of resource allocation—that adding more workers, running extra shifts, or paying premium fees will proportionally reduce the timeline. In some cases, this is true. In many cases, it is not. The constraint is not labor availability or machine capacity. The constraint is physics.

A powder-coated stainless steel tumbler requires a curing cycle of eighteen to twenty-four hours at a controlled temperature. This is not a policy. It is a chemical process. The powder coating is applied electrostatically, and the part is placed in a curing oven where the powder melts, flows, and cross-links into a durable finish. If the part is removed from the oven after twelve hours instead of twenty-four, the coating will not fully cure. It will remain soft, it will scratch easily, and it will fail quality inspection. The buyer can offer to pay double, triple, or ten times the standard rate, but the curing time cannot be reduced. The oven temperature cannot be increased beyond the specified range without degrading the coating. The part must remain in the oven for the full cycle, and there is no workaround.

The same principle applies to vacuum insulation. A double-wall stainless steel bottle is constructed by welding an inner shell to an outer shell, evacuating the air from the space between the two walls, and sealing the vacuum port. After welding, the bottle must undergo a stress-relief annealing process, which involves heating the assembly to a specific temperature and allowing it to cool slowly over forty-eight hours. This process eliminates residual stresses in the weld joints and prevents micro-cracks that could compromise the vacuum seal. If the cooling cycle is shortened, the weld integrity is compromised, and the bottle will fail vacuum retention testing. The buyer can request expedited delivery, but the annealing cycle cannot be compressed. The metallurgical process dictates the timeline, and no amount of labor or equipment can override it.

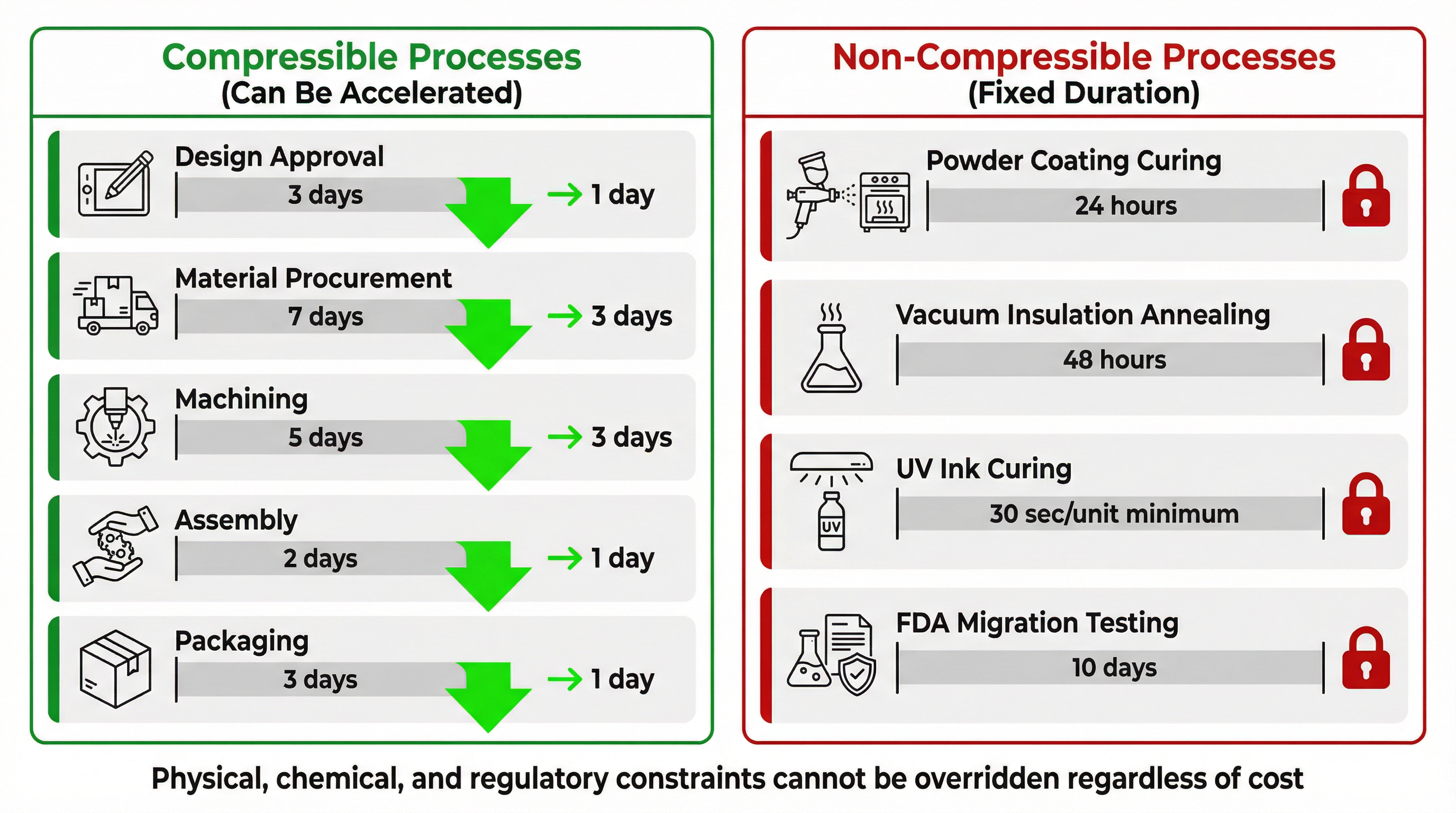

The buyer does not see these processes. The buyer sees a six-week lead time and assumes that every day within that six weeks is negotiable. The buyer does not distinguish between compressible time and non-compressible time. Compressible time includes activities that can be accelerated through additional resources: design approval, material procurement, machining, assembly, packaging. Non-compressible time includes activities governed by physical or chemical laws: curing, annealing, drying, cooling, testing. When a buyer requests a two-week reduction in a six-week lead time, the buyer is implicitly asking the factory to eliminate thirty-three percent of the timeline. If twenty percent of that timeline is non-compressible, the factory must eliminate forty percent of the compressible portion, which may not be feasible even with unlimited resources.

The misjudgment occurs because buyers conflate manufacturing with logistics. In logistics, expedited delivery is a matter of cost. A shipment that would normally take five days via ground freight can be delivered in two days via air freight, at a higher price. The buyer pays the premium, and the timeline compresses. The buyer applies the same logic to manufacturing, assuming that production is similarly elastic. But production is not logistics. Production involves transformations—chemical reactions, phase changes, material bonding—that occur at rates determined by thermodynamics, not by budget.

Consider the case of a buyer who orders custom-printed insulated tumblers with a full-color UV-cured ink design. The UV curing process exposes the printed surface to ultraviolet light, which triggers a photochemical reaction that hardens the ink. The curing time is approximately thirty seconds per part under a UV lamp. The buyer might assume that this is a fast process, and it is, relative to other curing methods. But the factory is producing two thousand units. At thirty seconds per unit, the total UV curing time is sixteen hours and forty minutes. The factory operates two UV curing stations, which reduces the time to eight hours and twenty minutes. The buyer requests a rush order and asks if the factory can cut the curing time in half. The factory cannot. The UV exposure time is calibrated to ensure complete polymerization of the ink. Reducing the exposure time will result in under-cured ink that remains tacky, smudges during handling, and fails adhesion testing. The factory can add a third UV curing station, which would reduce the time to five hours and thirty-three minutes, but this requires capital investment and assumes that a third station is available. The factory cannot reduce the per-unit curing time below thirty seconds without compromising quality.

The buyer may also request expedited FDA compliance testing. The buyer assumes that the testing laboratory can prioritize the order and deliver results faster if the buyer pays a rush fee. In some cases, this is true. The laboratory may offer expedited turnaround for an additional charge, reducing the standard ten-business-day timeline to five business days. But the laboratory cannot reduce the timeline below the minimum required for the test protocol. A migration test for food contact materials involves immersing the sample in a food simulant at an elevated temperature for a specified duration—often ten days—and then analyzing the simulant for extractable substances. The ten-day immersion period is mandated by FDA regulations. The laboratory cannot shorten it. The buyer can pay for expedited sample processing, expedited analysis, and expedited report generation, but the ten-day immersion period remains fixed. The total timeline may be reduced from fifteen business days to twelve business days, but it cannot be reduced to five business days, regardless of cost.

The buyer who does not understand these constraints will consistently overestimate the factory's ability to compress lead time. The buyer will assume that a six-week lead time can be reduced to four weeks with a twenty percent rush fee, and will be surprised when the factory explains that the maximum achievable reduction is one week, and only if certain conditions are met. The buyer will interpret this as inflexibility or lack of effort, when in fact it is a reflection of physical reality.

The factory's challenge is to communicate these constraints without appearing uncooperative. The factory must explain that some portions of the lead time are compressible and some are not, and that the compressible portions have already been optimized. The factory must also explain that compressing the compressible portions has diminishing returns. If the factory normally allocates two days for machining and one day for assembly, the factory can reduce machining to one day by running a second shift, but the factory cannot reduce it to zero. The factory can reduce assembly to half a day by adding workers, but the factory cannot eliminate it entirely. The cumulative effect of these reductions may shorten the lead time by one week, but not by two weeks, and certainly not by three weeks.

The buyer who understands this dynamic will approach rush orders differently. Instead of asking "Can you cut the lead time in half?", the buyer will ask "Which portions of the lead time are compressible, and what is the maximum feasible reduction?" The buyer will also ask "What are the cost implications of each level of acceleration?" and "What are the quality risks associated with compressing the timeline?" These questions reflect an understanding that lead time is not a single variable, but a composite of multiple processes, each with its own constraints.

The buyer who does not understand this dynamic will continue to treat lead time as a negotiable parameter, and will continue to be disappointed when the factory cannot deliver on unrealistic timelines. The buyer will blame the factory for poor planning or lack of capacity, when in fact the issue is a fundamental misalignment between the buyer's expectations and the physical limits of the manufacturing process.

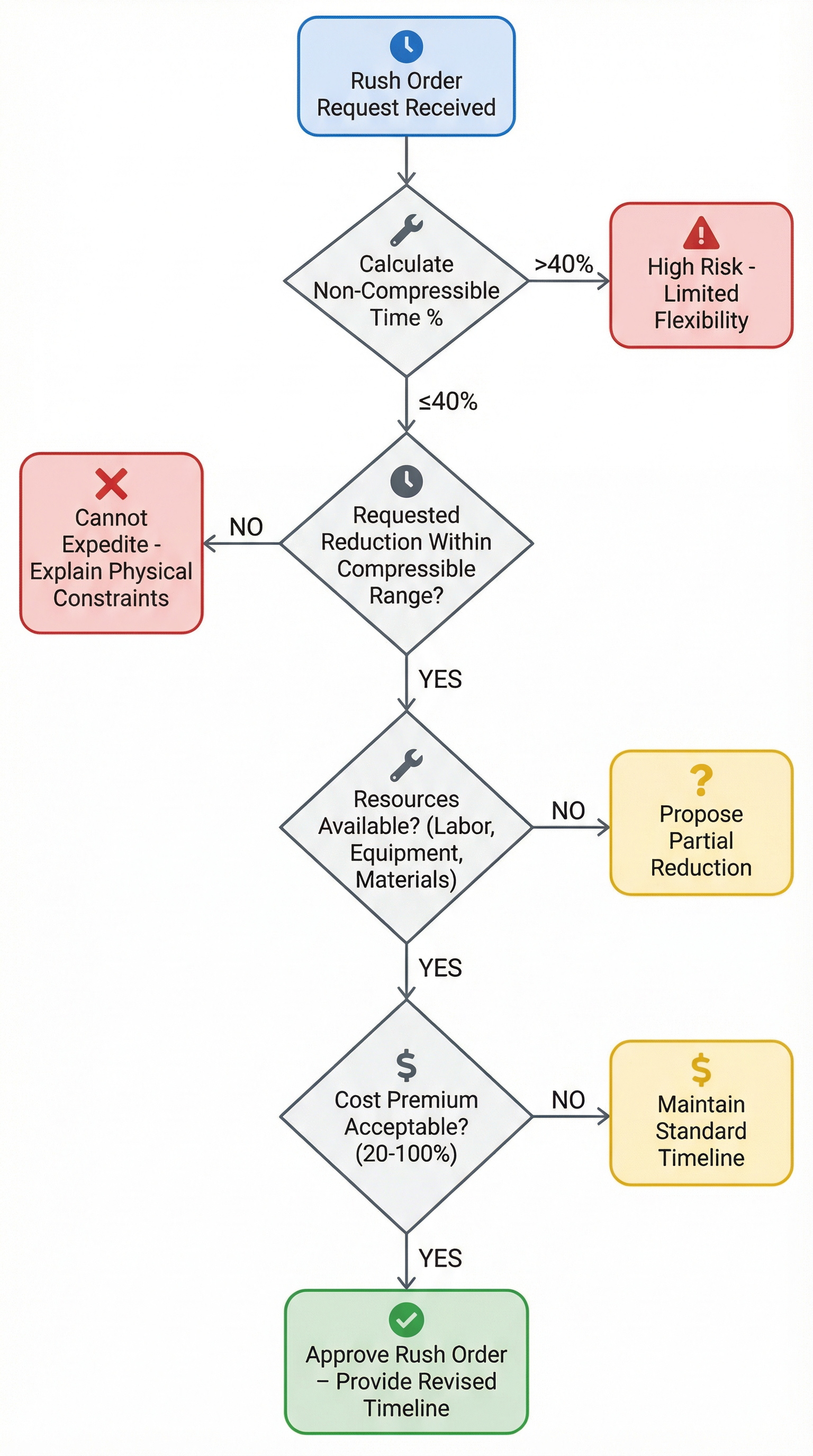

The solution is not to refuse rush orders. Rush orders are a commercial reality, and factories that can accommodate them gain a competitive advantage. The solution is to establish a clear framework for evaluating rush order feasibility. The factory should identify which processes are compressible and which are not, and should quantify the maximum achievable reduction for each compressible process. The factory should also identify the cost and quality implications of each level of acceleration. This framework allows the factory to respond to rush order requests with specific, data-driven answers, rather than vague assurances or blanket refusals.

For example, a factory producing custom drinkware might establish the following framework: Design approval can be compressed from three days to one day if the buyer provides immediate feedback. Material procurement can be compressed from seven days to three days if the factory maintains safety stock or if the supplier offers expedited delivery. Machining can be compressed from five days to three days by running a second shift. Powder coating requires a twenty-four-hour curing cycle that cannot be reduced. Assembly can be compressed from two days to one day by adding workers. FDA testing requires a minimum of twelve business days, including a ten-day immersion period that cannot be shortened. Packaging and shipping can be compressed from three days to one day by using air freight instead of ground freight.

Using this framework, the factory can calculate that a standard six-week lead time (forty-two days) can be reduced to a minimum of thirty-two days under ideal conditions, assuming that all compressible processes are accelerated and that the buyer accepts the associated cost increases. The factory cannot reduce the lead time below thirty-two days without compromising quality or regulatory compliance. If the buyer requests a four-week lead time (twenty-eight days), the factory must decline, because the non-compressible portions of the timeline alone account for more than twenty-eight days.

This level of transparency benefits both parties. The buyer gains a realistic understanding of what is achievable, and can plan accordingly. The factory avoids committing to timelines that cannot be met, and avoids the reputational damage that results from missed delivery dates. The buyer may still be disappointed that the lead time cannot be reduced as much as desired, but the buyer will understand why, and will not interpret the factory's response as a lack of effort or flexibility.

The broader lesson is that lead time is not a monolithic variable. It is a composite of multiple processes, some of which are elastic and some of which are rigid. The buyer who treats lead time as a single negotiable parameter will consistently misjudge the factory's ability to compress it. The buyer who understands the distinction between compressible and non-compressible time will make more informed decisions, will set more realistic expectations, and will avoid the frustration that comes from requesting the impossible.

The diagram above illustrates the distinction between compressible and non-compressible processes in custom drinkware manufacturing. Compressible processes—such as design approval, material procurement, machining, assembly, and packaging—can be accelerated through additional labor, equipment, or expedited logistics, typically at a cost premium of 20-50%. Non-compressible processes—such as powder coating curing (24 hours), vacuum insulation annealing (48 hours), UV ink curing (30 seconds per unit minimum), and FDA migration testing (10 days)—are governed by physical, chemical, or regulatory constraints that cannot be overridden regardless of cost. The buyer who requests a 50% lead time reduction must understand that if 40% of the timeline is non-compressible, the factory must eliminate 83% of the compressible portion, which is often impossible even with unlimited resources.

The second diagram provides a decision framework for evaluating rush order feasibility. When a buyer requests lead time compression, the factory must first calculate the percentage of the timeline that is non-compressible (typically 30-40% for custom drinkware). If the requested reduction exceeds the compressible portion, the order cannot be expedited without compromising quality or compliance. If the requested reduction is within the compressible range, the factory must assess whether sufficient resources (labor, equipment, materials, logistics capacity) are available to achieve the acceleration. If resources are available, the factory can provide a cost estimate (typically 20-50% premium for moderate acceleration, 50-100% premium for maximum acceleration). If resources are not available, the factory must decline or propose a partial reduction. This framework prevents the factory from committing to unachievable timelines and helps the buyer understand the practical limits of lead time compression.