When a procurement manager secures a supplier agreement for 500 custom stainless steel tumblers with an eight-week lead time quoted at $18.50 per unit—a 27% premium over the $14.50 standard price for orders meeting the 1,000-unit minimum—the assumption is straightforward. The premium compensates the supplier for the inefficiency of a smaller production run, and in exchange, the buyer receives a guaranteed production slot with the quoted timeline. Three weeks after order confirmation and deposit payment, the procurement manager receives an apologetic email explaining that the order will be delayed by four weeks due to "unexpected production scheduling adjustments." The supplier offers no detailed explanation beyond citing "capacity constraints," leaving the buyer frustrated and confused. They had paid a significant premium specifically to secure flexibility on volume—why would the supplier now compromise on the one element that matters most: the delivery timeline?

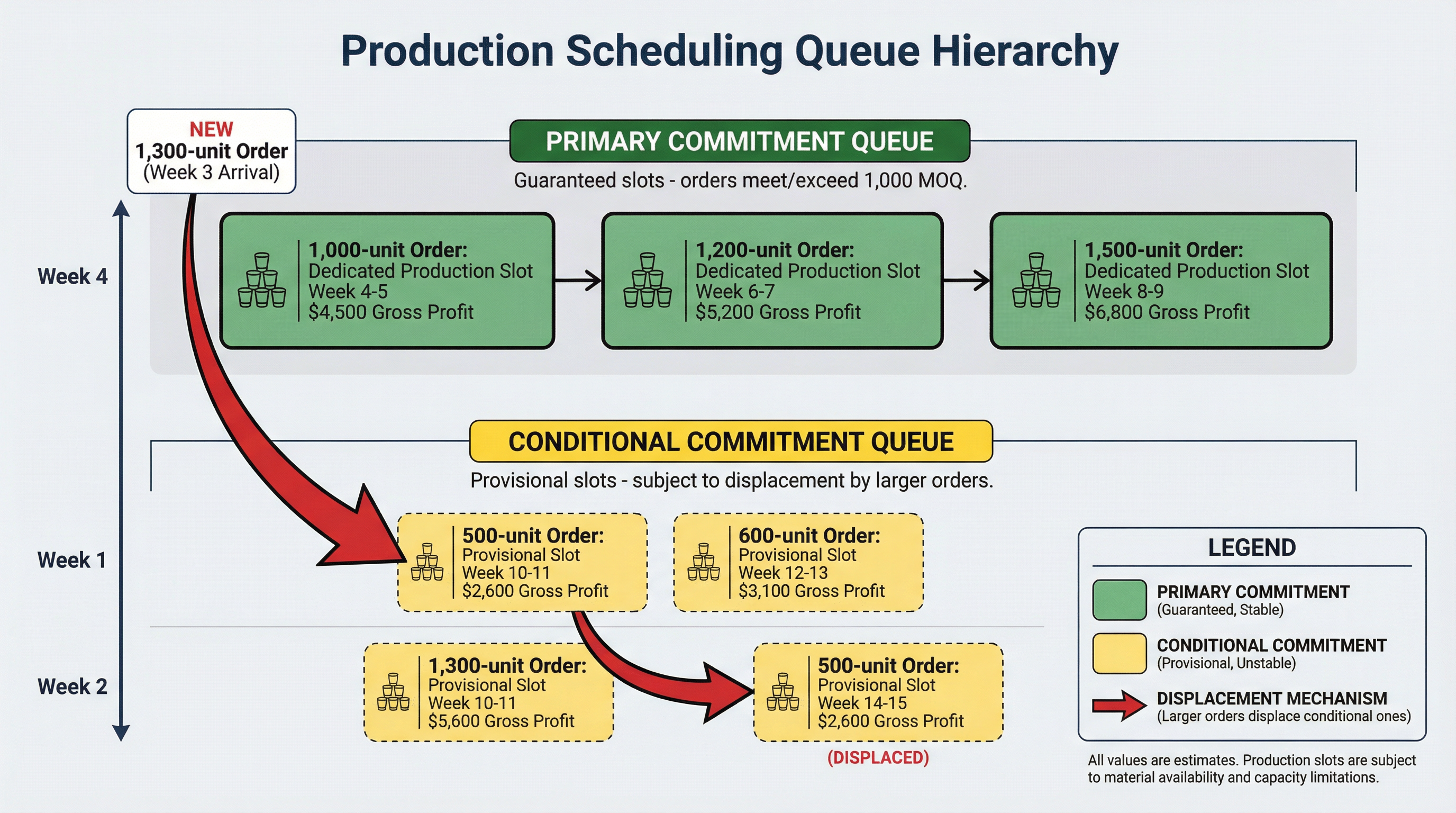

The delay is not caused by equipment failure, material shortage, or quality control issues. It is caused by how factories categorize and prioritize orders that fall below the stated minimum order quantity. Understanding this categorization requires recognizing that production scheduling in make-to-order manufacturing operates less like a queue at a bank—where the first person in line is served first—and more like an airline's standby list, where your position depends not on when you arrived but on the relative value you represent to the operator. When a factory accepts an order that meets or exceeds the stated MOQ, that order enters what production planners call the primary commitment queue. The factory allocates specific production capacity—equipment time, labor hours, quality control resources—to that order based on the lead time quoted. This allocation represents a genuine commitment because the order's profitability justifies the dedicated resources.

A 1,000-unit order for powder-coated stainless steel tumblers at $14.50 per unit generates $14,500 in revenue and approximately $4,200-4,800 in gross profit after accounting for materials ($6,500), labor ($2,200), and overhead ($1,600). The factory views this as a productive use of a six-to-seven-day production slot: two days for powder coating and curing, two days for laser engraving and assembly, one day for vacuum insulation processing and annealing, and one to two days for quality control and packaging. The profit margin of 29-33% aligns with the factory's target for standard production runs, and the order's size justifies the setup costs associated with powder coating equipment calibration, laser engraving file preparation, and vacuum chamber configuration.

Orders below the minimum threshold occupy a fundamentally different position in the scheduling hierarchy, even when the supplier quotes a specific lead time. These orders are categorized internally as conditional commitments. The factory intends to produce them within the quoted timeframe, but that intention is subordinate to the opportunity cost calculation that production managers perform continuously. When a 500-unit below-MOQ order at $18.50 per unit generates $9,250 in revenue and approximately $2,400-2,800 in gross profit, the factory must evaluate whether producing that order represents the best use of the production slot it would occupy. The mathematics of this evaluation become clear when a competing order arrives.

A procurement inquiry for 1,200 units at $14.00 per unit—slightly below the standard 1,000-unit price due to volume—generates $16,800 in revenue and approximately $5,000-5,600 in gross profit. From the factory's perspective, accepting this larger order means displacing the 500-unit order from its scheduled slot. The financial impact is straightforward: producing the 1,200-unit order instead of the 500-unit order increases gross profit by $2,600-2,800 for the same production capacity commitment. The factory does not view this as breaking a commitment to the smaller order; they view it as optimizing resource allocation in response to changing demand conditions. The 500-unit order is rescheduled to a later slot, typically the next available gap in the production schedule after all primary commitment orders are accommodated.

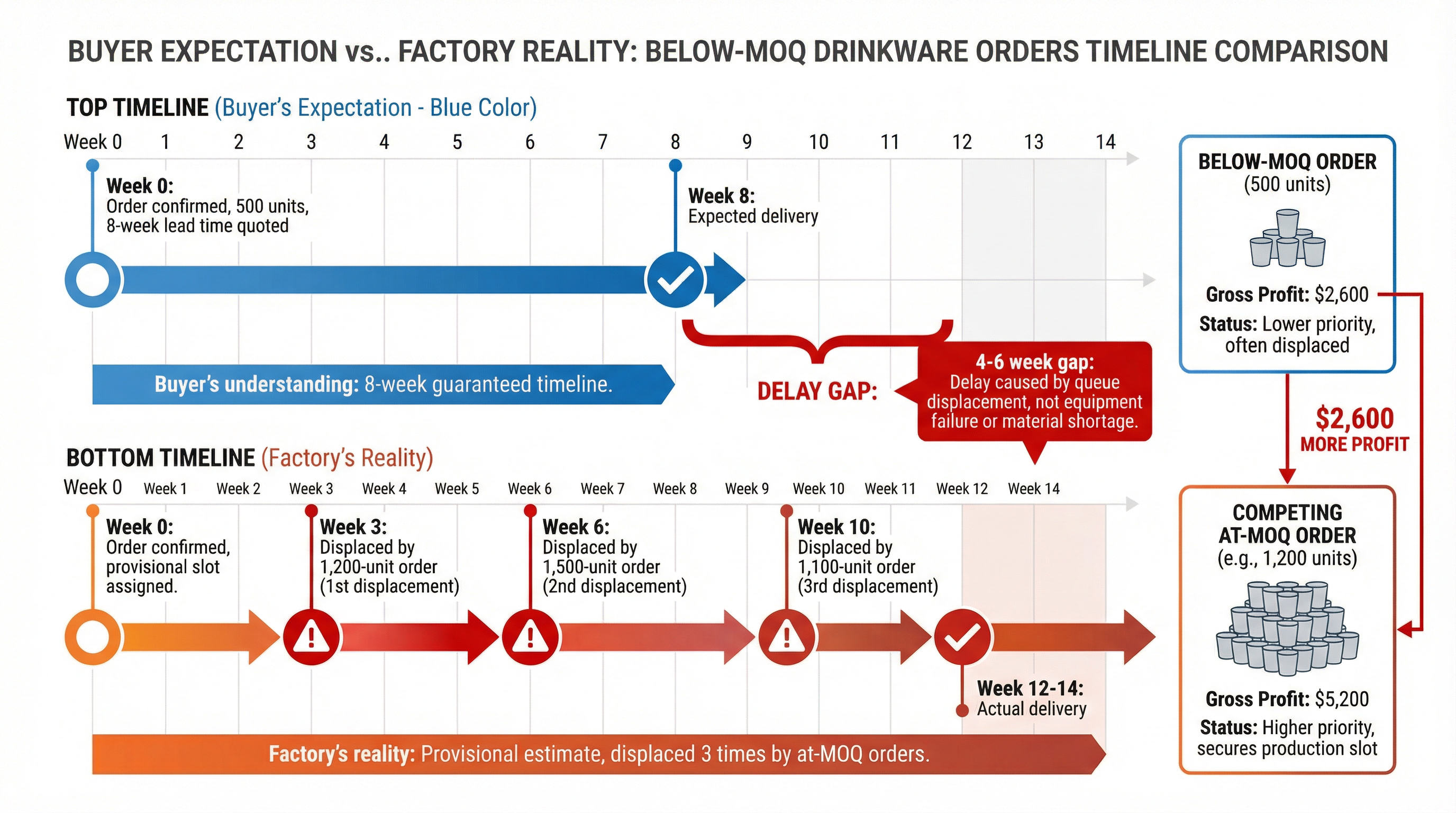

In practice, this is often where lead time decisions start to be misjudged. The disconnect between quoted lead times and actual delivery dates for below-MOQ orders stems from how factories communicate scheduling commitments. When a supplier quotes an eight-week lead time for a below-MOQ order, they are providing an estimate based on current capacity utilization and forecasted demand. This is not the same as the lead time quoted for an at-MOQ or above-MOQ order, which reflects a dedicated production slot. The distinction is subtle but consequential. For standard-volume orders, the lead time calculation works backward from available capacity. The factory identifies the next available production slot that can accommodate the order's requirements, accounts for material procurement time and any pre-production setup, and communicates that timeline to the buyer. Once the order is confirmed and the deposit is received, that slot is reserved. Subsequent inquiries for similar products are quoted lead times that account for the already-reserved capacity.

For below-MOQ orders, the lead time calculation works differently. The factory estimates when they could fit the order into their schedule based on anticipated gaps between larger orders or periods of lower demand. This estimate assumes that no higher-priority orders will arrive to claim those production slots. When such orders do arrive—and in most manufacturing environments, they arrive frequently—the below-MOQ order gets rescheduled. The factory does not view this as a broken commitment because, from their perspective, the below-MOQ order never had a guaranteed slot. It had a provisional estimate that was always subject to displacement by more profitable work.

The frequency of these displacements determines the actual lead time extension. In a factory operating at 75-85% capacity utilization—typical for custom drinkware manufacturers during non-peak periods—a below-MOQ order might be displaced once or twice before production begins, extending the original eight-week estimate to 10-12 weeks. In a factory operating at 90-95% capacity utilization—common during Q4 corporate gifting season—the same order might be displaced three to four times, extending the timeline to 12-14 weeks or longer. Each displacement occurs because a more profitable order arrives and claims the production slot that the below-MOQ order was tentatively assigned. The factory prioritizes the higher-value work, and the smaller order moves to the next available gap.

This scheduling logic explains why paying a premium for below-MOQ orders does not guarantee timeline reliability. The premium compensates for the higher per-unit production cost—the inefficiency of running a powder coating line for 500 units instead of 1,000, the setup time for laser engraving that is amortized over fewer units, the quality control labor that represents a larger percentage of total production time. It does not, however, purchase a guaranteed production slot. That guarantee is implicitly reserved for orders that meet or exceed the MOQ, where the profitability justifies the dedicated capacity allocation. Buyers who assume that the premium secures both cost recovery and timeline commitment are operating under a misunderstanding of how production scheduling priorities function on the factory floor.

The challenge for buyers is that suppliers rarely make this distinction explicit during the quotation process. When a supplier quotes an eight-week lead time for a 500-unit order, the quote document typically does not specify that this timeline is a provisional estimate subject to displacement by larger orders. The language used—"lead time: 8 weeks"—appears identical to the language used for at-MOQ orders, even though the underlying commitment level is fundamentally different. This communication gap creates the expectation mismatch that leads to frustration when delays occur. The buyer interprets the quoted lead time as a firm commitment, while the supplier interprets it as a best-case estimate that assumes no higher-priority orders will arrive during the production window.

The impact of this misjudgment extends beyond the immediate delivery delay. When a buyer plans a product launch, corporate event, or seasonal campaign around an eight-week lead time and discovers in week three that the actual timeline is now 12-14 weeks, the operational consequences can be significant. Marketing materials may need to be revised, event logistics may need to be rescheduled, and alternative suppliers may need to be engaged on an expedited basis—often at a cost premium that exceeds the savings from the original below-MOQ order. In some cases, the delay forces the buyer to cancel the order entirely and source from a distributor with existing inventory, accepting a higher per-unit cost ($22-24 per unit for stock tumblers) to meet the original deadline.

The solution for buyers is not to avoid below-MOQ orders entirely, but to recognize that these orders require a different approach to timeline planning. When ordering below the MOQ, the quoted lead time should be treated as a minimum estimate rather than a maximum commitment. Adding a buffer of 30-50% to the quoted timeline—turning an eight-week quote into a 10-12 week planning horizon—accounts for the realistic probability of one or two scheduling displacements. For time-sensitive orders where the deadline is non-negotiable, buyers should either meet the MOQ to secure a primary commitment slot or negotiate a premium that explicitly includes a guaranteed production slot. Some factories offer this option at a 15-20% additional cost above the standard below-MOQ premium, effectively purchasing insurance against displacement.

Another approach is to structure orders in a way that aligns with the broader structure of manufacturing timelines, where understanding the distinction between provisional and dedicated capacity allocations becomes part of the procurement strategy. For buyers who regularly order below the MOQ, establishing a framework agreement with the supplier that specifies minimum annual volume can shift the relationship from transactional to strategic. A buyer who commits to 3,000 units per year across six orders of 500 units each may be able to negotiate primary commitment status for those orders, even though each individual order falls below the 1,000-unit MOQ. The annual volume justifies the dedicated capacity allocation, and the factory can plan its production schedule around the predictable demand.

The distinction between primary and conditional commitment orders also explains why some suppliers refuse to accept below-MOQ orders during peak demand periods. When a factory is operating at 95-100% capacity utilization, every production slot is occupied by primary commitment orders, and there are no gaps available for conditional commitment work. Accepting a below-MOQ order during this period would mean either displacing an at-MOQ order—which would damage the supplier's relationship with a higher-value customer—or quoting a lead time so extended that the buyer would likely decline. Rather than quote a 16-18 week lead time for a 500-unit order, many suppliers simply decline the inquiry and suggest the buyer return during a lower-demand period or increase the order quantity to meet the MOQ.

For buyers who discover mid-production that their below-MOQ order has been displaced, the options for acceleration are limited. Offering to increase the order quantity to meet the MOQ after the fact rarely changes the production schedule, because the factory has already allocated the displaced slot to another order. The most effective intervention is to negotiate a split delivery, where the factory produces a partial quantity—typically 200-300 units—as a rush order to meet the immediate deadline, with the remaining units delivered on the extended timeline. This approach requires paying a rush premium (typically 25-35% above the already-elevated below-MOQ price) for the partial quantity, but it allows the buyer to proceed with the planned event or campaign while waiting for the full order to be completed.

The misjudgment around below-MOQ lead times is not a failure of supplier integrity or buyer diligence. It is a structural consequence of how production scheduling operates in make-to-order manufacturing, where capacity is allocated based on profitability and the relative value of competing orders. Buyers who understand this structure can plan accordingly, either by meeting the MOQ to secure a guaranteed slot, by adding timeline buffers to account for displacement risk, or by negotiating explicit guarantees that remove the order from the conditional commitment queue. Suppliers who make this structure explicit during the quotation process—clearly distinguishing between provisional estimates for below-MOQ orders and firm commitments for at-MOQ orders—can reduce the expectation mismatch that leads to frustration and relationship damage when delays occur. The premium paid for below-MOQ orders compensates for production inefficiency, but it does not automatically purchase timeline certainty. That certainty requires either meeting the minimum threshold or negotiating a separate commitment that explicitly addresses the scheduling priority.